Ownership is a feature unique to rust, enabling memory safety, without a garbage collector.

What Is Ownership?

All programs must manage the way they use a computers memory while running.

Some languages use a GC, or garbage collector: A garbage collector automatically frees up memory that a program isn't using anymore., whereas other languages require you to explicitly manage the memory your program will use.

Rust takes a different approach- memory is managed via an ownership system, with a set of rules the compiler checks at compile time.

The Stack and The Heap

In a language like Rust, whether a value is on the stack or #heap, has a more direct effect on how the code behaves, and your decision making.

Both the stack and the heap are parts of memory that are available to your code at runtime, but they're structured differently.

The stack stores values in the order it receives them, and returns them in the opposite order, in a #LIFO manner.

You push data onto the #stack, and pop data off of the stack.

All data on the stack must have a known, fixed size, meaning if the size is unknown at runtime, or might change during runtime, it must be stored on the #heap.

A #heap is less organized: when you put data on the heap, the operating system places that data in a random spot that is big enough to store it, and returns a pointer to that location. This is usually referred to as allocation, because you are implicitly allocating an amount of memory for storing data.

Pushing to the stack is faster, because the OS knows where to put it: wherever the stack is stored. Allocating heap space requires more work, because the OS has to find that space. Contemporary processors may be faster if they jump around less in memory (((Xigdv5YRN)) This is because Computers are tuned to get an extra speed boost when reading memory addresses that're close to each other. ) (See [[RAM]]). Even though the memory controller can jump between far-apart memory addresses quickly, programs tend to access memory that's nearby. Thusly, the stack is usually quicker.

Keeping track of what parts of your code use stack vs heap space, deduping heap data, and more, are all problems that ownership addresses.

Ownership Rules:

Each value in Rust has a variable that's called its owner.

There can only be one owner at a time.

When the owner goes out of scope, the value will be dropped.

Variable Scope

A scope is the area within a program in which a variable is valid.

#![allow(unused_variables)]

fn main() {

let s = "hello";

}fn main() {

{// s is not valid here, it’s not yet declared

let s = "hello";// s is now valid

// do stuff with s

}// this scope is over, s is no longer valid

}In other words, there are two points in a variables existence: when it comes into scope (becomes valid), and when it goes out of scope (becomes invalid).

The String Type

Rust has a str type in the core language, and a String type, provided in the standard library, which is a string literal.

String literals aren't suitable for every situation that requires text- they're immutable. Also, every possible string value can't be known before hand, if you think about things like user input.

In these situation, String, is used, and is allocated on the heap, allowing us to store a non-deterministic amount of text, that can be unknown at compile time.

You can create a String from a str using String::from(str), and the double colon allows us to namespace a function, in this case from, (to use without collisions with other functions named from).

Via String::from(), we request the required memory from the memory allocator.

These kinds of strings can be mutated.

The difference is how these two types deal with memory- string literals have a known size at compile time, and thus can be stored on the stack, but when we don't, we have to store on the heap, in order to allocate memory dynamically.

There's a natural point at which the memory allocated for String can be returned- when the variable that owns the value goes out of scope. When this takes place, Rust calls an internal function, drop, for us, and this performs the job of C's free, which is done with #GC.

Ways Variables & Data Interact: Move

let x = 5;

let y = x;The value 5 is bound to x, and the value x is bound to y.

(Note that both instances of the value 5 are pushed onto the stack here). The value is copied.

Now, let's look at the String version:

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let s2 - s1;While this code looks similar to the code above, they don't operate in the same way, memory wise.

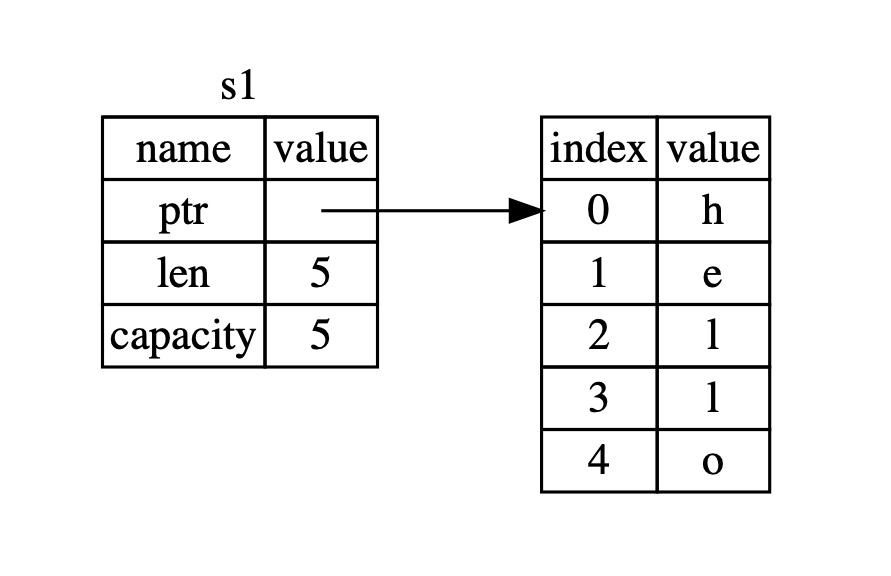

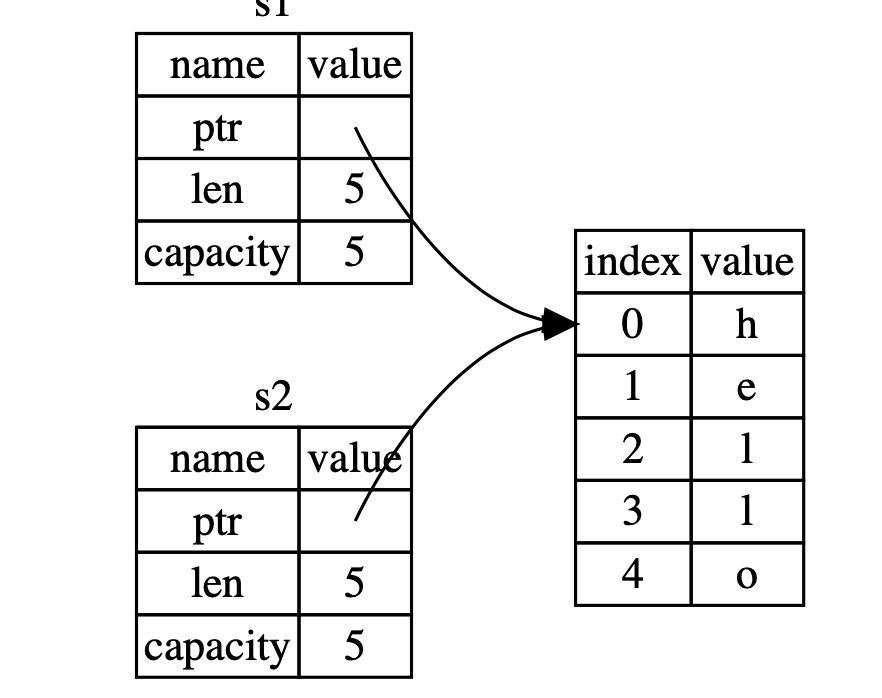

A String is composed of a pointer to the memory holding the contents of the string, a length, and a capacity. The length is the number of bytes required to store the string. When we assigned s1 to s2, the String data is copied (length, and capacity), but not the data on the heap (differing between Stringdata & Stringcontent).

Part of the reason for this is that the copying operation could become expensive or unperformant depending on the size of the data on the heap.

However, we're now faced with a problem:

When a variable goes out of scope, Rust calls drop and, and cleans up the memory for that variable. In the case of s1 & s2, they both go out of scope simultaneously, and thus would end up trying to free the same piece of memory, resulting in a double free error.

To combat this, Rust simply invalidates s1, thus removing the need to free anything when it goes out of scope.

Rusts invalidation of s1, while keeping s2 valid, is called a move, in that the data in s1 was moved into s2.

Rust will never automatically create deep copies of data.

Ways Variables & Data Interact: Clone

If we do want to deeply copy heap data, we can use clone.

Stack-Only Data: Copy

let x = 5;

let y = x;

println!("X is: {}, y is: {}", x,y);While it seems contradictory, that we don't have to call clone, thre is a reason.

Integer types have a size that is known at compile time, so they are stored entirely on the stack, and thus copies are easy to make.

Rust provides a special annotation called the Copy trait, that we can place on integers on the stack. If a type has the Copy trait, an older variable may still be useable after assignment.

We can't annotate a type with Copy if the type, or any of its sub-types have implemented the Drop trait.

Generally, any scalar values are copy (or groupings), as well as anything that doesn't need to be allocated on the heap.

Ownership and Functions

fn main() {

let s = String::from("hello"); // s in scope

takes_ownership(s); // s moved into function

// s is no longer valid

// if we tried to use s here, we'd get a

// compile-time error.

let x = 5; // x is in scope

makes_copy(x); // x *would* move into function

// but integers are copy, so x remains valid.

}// now x goes out of scope, then s, but since s'

// value was moved, nothing special happens.

fn takes_ownership(some_string: String) { // some_string in scope

println!("{}", some_string);

} // some string goes out of scope and drop is called.

// The memory is now freed.

fn makes_copy(some_integer: i32) {

println!("{}", some_integer);

} // some integer leaves scope, but nothing happens

// because copy.Return Values and Scope

The semantic for passing a value are similar to those for assigning values to variables. Passing a variable will move or copy (data) just as assignment does.

fn main() {

let s1 = gives_ownership();

// gives_ownership moves it's return value

// into s1

let s2 = String::from("hello"); // s2 in scope

// s2 is moved into takes_and_gives_back

// which moves it's value into s3

let s3 = takes_and_gives_back(s2);

} // Here, s3 goes out of scope, and is dropped

// while s2 remains untouched because it's value was moved.

// was moved.

//

fn gives_ownership() -> String {

// gives_ownership will move it's return value

// into the function that calls it.

let some_string = String::from("hello"); // some string in scope

some_string // returned to calling function.

}

fn takes_and_gives_back(a_string: String) -> {

a_string

}The ownership of a variable follows a pattern: assigning a value to another variable moves it. When a variable includes data on the heap, and goes out of scope, the value will be cleaned up my drop (the allocated memory returned to the memory allocator).

Taking ownership with every function is tedious, so there are ways to let a function use a borrow without owning it. Basically, borrowing.

References and Borrowing

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let (s2, len) = calculate_length(s1);

println!("The length of '{}' is {}.", s2, len);

}

fn calculate_length(s: String) -> (String, usize) {

let length = s.len(); // len() returns the length of a String

(s, length)

}The issue with this code, is that this process of returning multiple values that are owned elsewhere, is tedious. There's an easier way, which is to use &, which indicates a reference to an object. As using & creates a reference, we necessarily need a method for dereferencing objects, which comes from the trusty *, given to us from C. The & syntax also effects the return signature of a function, as well as the parameter type. Borrowed values are not mutable, by default, but mutable references can be created by appending the ampersand and mut keyword, &mut.

The catch, or tradeoff here, is that a piece of data can only have one mutable reference per scope. This allows for a strict, but controlled mutation, which prevents a data race.

A #data-race is a type of race condition that occurs when:

Two or more pointers access the same data simultaneously.

At least one of the pointers is writing data.

There's no mechanism for synchronizing access.

Data races cause undefined behavior, and can be difficult to diagnose and fix during runtime.

We can use curly brackets to initiate a new scope, allowing for multiple references, as opposed to simultaneous ones.

There is a similar rule, which is that you can't have mutable and immutable references to the same piece of data.

Though this may be possible via creating a new scope(?).

Update: it is.

The Slice Type

Another data type that doesn't have ownership is the slice.

This type allows for referencing a contiguous sequence of elements in a collection, as opposed to a whole collection.

Here’s a small programming problem: write a function that takes a string and returns the first word it finds in that string. If the function doesn’t find a space in the string, the whole string must be one word, so the entire string should be returned.

Let's think about the signature of this function:

fn first_word(s: &String) -> ? The question is, what should we return? We don't want the whole string, and we also don't want to take ownership of it.

fn first_word(s: &String) -> usize {

let bytes = s.as_bytes();

for (i, &item) in bytes.iter().enumerate() {

if item == b' ' {

return i;

}

}

s.len()

}We need to go over the string element by element (nice syntactic sugar on pointer arithmetic guys), and check values, we convert it to an array of bytes, over which we create an iterator, with iter(). enumerate wraps the result of iter and returns each element as a tuple instead. The first element is the index, the second a reference to the element.

Enumerate returns a tuple, allowing us to use pattern matching to destructure it.

We now have a problem: when the value of s.len() is returned, there's no meaningful string to use it with- the values are decoupled. We'll have the value of the length, but the string it came from will be entirely invalidated, as we're operating on a slice, which has no ownership to pass around to functions, meaning it's lifetime isn't extended by moves.

String Slices

We create these slices using a reference and range, with an inclusive starting index, and an exclusive ending index.

Internally, this structure stores the starting index and the length.

The type that signifies a string slice is written as &str.

This will allow us to get back a value that is tied to the data it came from.

Remember if we have an immutable reference to a thing, we can't make a mutable reference (within the same scope).

We can also use this type as a parameter, allowing us to use the same function on &String and &str values.